Washington Court of Appeals rules on case involving homeless man arrested in Vancouver

News story in The Columbian newspaper.

By Jessica Prokop, Columbian Courts Reporter and Patty Hastings, Columbian Social Services, Demographics, Faith

Published: October 10, 2017, 9:15 PM

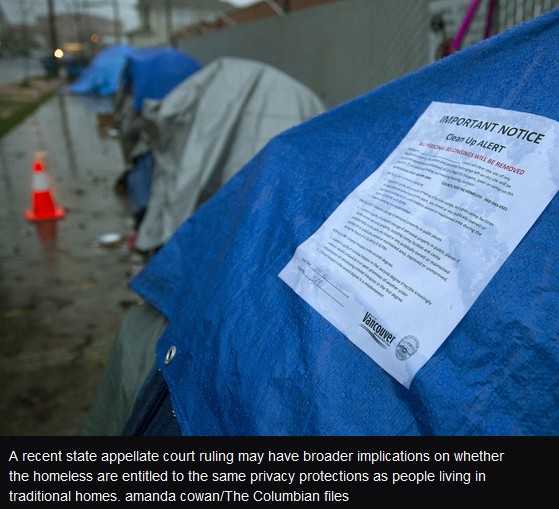

A homeless man staying in a makeshift shelter had an expectation of privacy under the Washington state Constitution — just like people in traditional homes — when police peeked inside his dwelling. That’s the finding of a Washington Court of Appeals opinion that was published in part Tuesday and could have broader implications on privacy rights for the homeless.

The decision affirms a Clark County Superior Court judge’s 2015 ruling that Vancouver police officers violated William R. Pippin’s privacy rights when they looked inside his tarp, despite him being camped illegally in downtown Vancouver.

Pippin was subsequently charged with methamphetamine possession, but his case was dismissed after Judge Scott Collier granted the defense’s motion to suppress the drug as evidence, because Pippin’s privacy rights were violated.

However, the appeals court also ruled that Pippin’s case should be remanded to Superior Court after reversing part of Collier’s ruling. In the unpublished portion of the opinion, the appeals court found that Collier used the incorrect legal standard for determining whether exigent circumstances of officer safety justified them looking inside Pippin’s dwelling without a warrant.

Pippin was arrested Nov. 2, 2015, and charged with methamphetamine possession after the officers contacted him about camping in public past the lawful time. Officers had pulled back his tarp entrance to look inside when he didn’t come out right away and heard him rustling around inside. In doing so, they saw some packaged methamphetamine.

Pippin’s defense attorney, Chris Ramsay, argued that although his client was camping illegally, officers still violated his Fourth Amendment rights when they looked inside his dwelling.

Tuesday’s decision does not analyze the Fourth Amendment, which looks at whether an individual’s expectation of privacy is reasonable. The appeals court instead analyzed the state’s constitution on privacy protection.

Ramsay said Pippin is still homeless, and if he’s called to court later, Ramsay has no idea how to reach him.

‘You have rights’

Doug Honig, spokesman for the American Civil Liberties Union of Washington, which weighed in on the case, said the organization is “pleased that the court agreed that the constitution applies to everyone.

“It doesn’t matter whether your home is a tarp and a couple of poles or a huge mansion, you have constitutional rights,” he said.

A pair of attorneys with the ACLU submitted an amicus brief last year addressing the constitutionality of entering and searching someone’s makeshift shelter, as well as the case’s impact on privacy rights for people experiencing homelessness. Seattle University School of Law’s Homeless Rights Advocacy Project, the Seattle-based publication Real Change, and the Vancouver-based homeless advocacy group Outsiders Inn were also named in the brief.

Adam Kravitz of Outsiders Inn was in downtown Vancouver the day police were contacting people camping around Share House, a men’s homeless shelter. Kravitz’s organization later became involved in another lawsuit about seizing homeless people’s personal property. Kravitz said he, too, is pleased to hear that the issue of privacy rights for homeless people is being understood and analyzed.

“This is very good news,” he said. “I think we’re finally making some headway on a really important issue.”

He noted that the decision comes at a time when the nights are getting colder and hundreds of people on the streets are going to need shelter.

“I believe that Washington state can be the leaders on changing homelessness rights,” Kravitz said. “All citizens have rights and we need to help them.”

Broad implications

Adam Gershowitz, a professor at Virginia’s William & Mary Law School, called the issue of privacy protection for the homeless “unchartered territory.”

“I applaud the idea that (the Washington Court of Appeals) found (privacy protection) under the state constitution,” Gershowitz said, adding that “state courts are free to take a more expansive interpretation under their state constitution.”

And although he said he’s no expert on Washington’s Constitution, he’s not surprised that the appeals court interpreted its state constitution on privacy protection more broadly than what the Fourth Amendment provides. But as a matter of the Fourth Amendment, Gershowitz said it’s hard to say if the court’s decision is right.

The homeless may have an expectation to privacy but that doesn’t mean society views it as reasonable, Gershowitz said. If a person doesn’t own or rent the space they are on, he said, then they are not entitled to be there, especially if it’s on public land.

“I wish we had more services for (the homeless),” Gershowitz said. “But at the end of the day, they don’t have a reasonable expectation (to privacy) when they can be moved from the spot by an officer.”

It’s likely that this decision will have broader implications in the state of Washington, Gershowitz said, and it suggests that the homeless have rights in other contexts when they put up quasi-dwellings.

In its opinion, the appeals court found that Pippin’s dwelling afforded him fundamental activities, such as “sleeping under the comfort of a roof and enclosure” and gave him some separation from the rest of the world. The court also found that the “temporary nature of Pippin’s tent does not undermine any privacy interest.

“Nor does the flimsy and vulnerable nature of an improvised structure leave it less worthy of privacy protections. For the homeless, those may often be the only refuge for the private in the world as it is,” the opinion reads.

A previous case cited in the opinion found that “the traditional home is not the only place in which a person should have privacy protection.”

The court determined that Pippin did not voluntarily expose his personal information to public scrutiny but acknowledged that some people may argue he did so by choosing to live in a tent on public land.

“Against this backdrop, to call homelessness voluntary, and thus unworthy of basic privacy protections is to walk blind among the realities around us. Worse, such an argument would strip those on the street of the protections given the rest of us directly because of their poverty. Our constitution means something better,” the panel wrote.

Collier said in a phone interview that under the facts of this case, he felt Pippin had an expectation of privacy and acknowledged there are possible broader implications from the appeals court’s decision.

“It gives some guidance to other courts that may have to wrestle with this issue but is still case-fact specific,” he said.

He declined to go into specifics about the future of the case, regarding the warrantless search and protective sweep element.

‘A solid ruling’

Ramsay, Pippin’s defense attorney, said he is happy that the court sided with Collier on the privacy issue.

“I always knew in my heart of hearts that legally that was a very solid ruling by Judge Collier. The way the transient population is these days just because they’re poor and don’t have anything doesn’t mean they don’t have the same privacy rights as everybody else,” Ramsay said. “They have a right to go into an enclosure for privacy to get a night’s sleep or not have to deal with people.”

Deputy Prosecutor Rachael Probstfeld with the Clark County Prosecuting Attorney’s appellate unit said she does not yet know if the office will seek review of the appeals court’s decision by the state Supreme Court.

‘Trial court erred’

In its brief on appeal, the prosecution argued that “the trial court erred in finding Pippin had a reasonable expectation of privacy in a tarp structure on public property located on the side of a road between a guardrail and the fence of a private property.

“No reasonable person would have an expectation of privacy in a location where he is openly committing a crime on public property during daylight hours,” the prosecution wrote in its brief.

City Prosecutor Kevin McClure reflected on how the ruling would impact the way Vancouver police officers go about entering somebody’s makeshift shelter.

“The court’s decision was pretty clear that it may require a warrant,” McClure said. “I think that’s a fairly narrow situation for most police officers to be in.”

Typically, he said, when police ask to talk with people who are inside tents or tarps, people often just do what the officer says. It’s just like when a police officer knocks on the door of somebody’s house; most times those people just open the door and respond to the officer, McClure said.

Link to original story posted in The Columbian here: